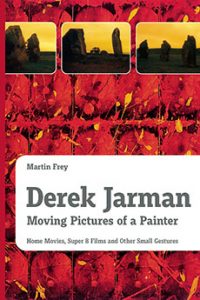

Derek Jarman, who completed a degree in painting and stage design at London’s Slade School of Art, became known to a broader public primarily through the medium of film. However, he never saw himself as a film-maker and also a painter but always as primarily a painter. Painting was his most important and direct medium of expression, his ‘lifeline’: the filmic images are the moving pictures of a painter. The first edition of Derek Jarman – Moving Pictures of a Painter was published in German in 2008. It was the first work in German to deal in depth with the works of Jarman.

In terms of content, it is primarily an examination of Jarman’s lesser known and – at first glance – not readily accessible work in the area of home movies and Super 8 films as well as the ‘cinema of small gestures’ he developed out of them. The English translation is based on the unaltered original text. Only the bibliography and filmography have been expanded and supplemented. (…)

Life and work: an indivisible unity

For Jarman, life and work represented an indivisible unity that immediately and directly manifested itself in every area of his work as an artist, by way of autobiographical elements and points of reference. His numerous texts and publications are thus among the central and most important sources for this book – with their subjective mode of expression always taken into account. In particular his two books Dancing Ledge and The Last of England, which were published in the mid-eighties, provide a great number of valuable details about the history of his Super 8 films’ creation and their background.

However, along with Modern Nature (1991) and At Your Own Risk (1992), these books primarily provide very personal information about his childhood and adolescence in post-war England, which he experienced as repressive, and his coming out during his studies as well as the liberated life of the seventies. They also provide detailed information about his struggle against the permanent repression and unequal treatment of homosexuals during the Thatcher era, about how he dealt with his own HIV infection and later illness and about his personal commitment to combating discrimination against people infected with HIV or suffering from Aids.

Autobiographical elements

The direct presence of autobiographical elements in his works therefore stands at the centre of my examination of his work. Thus, an initial attempt to more closely grasp Jarman’s individual understanding of the home movie in connection with the concept of ‘home’ is carried out in the chapter ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow – Images of Childhood’. He integrated numerous sequences from the store of his parents’ and grandparents’ 8 mm films into his film THE LAST OF ENGLAND; in this way, he provides us with very personal glimpses into his own (family) history.

In an environment constantly experienced as hostile, Jarman himself gradually developed isolated islands of individual strategies, which I refer to as the ‘strategy of the autobiographical’ and the ‘strategy of naming’. In this context painting became the first form that he explored, and it was originally primarily an opportunity to withdraw into a free space created by himself.

Influences from painting and literature

Chapter 3 explores the question of influences from the fields of painting and literature on his work. The Beat Generation, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Rauschenberg, David Hockney and Yves Klein – above all, however, his first journeys to America – produced a lasting resonance. A multilayered dissolution of boundaries becomes manifest in every area of Jarman’s work: collage techniques, associative elements of the fragmentary and the open narrative forms inherent to them become elemental means of communication in his paintings, films and texts.

Throughout his life Jarman nonetheless vehemently resisted the attempts made to categorise him, particularly with regard to his filmic work. He was always focused on his desire to visually realise a message; the appropriate medium was selected during the search for the form of realisation corresponding to the given case. Classifications by means of keywords, such as ‘avant-garde film’ or ‘experimental film’ lead to a dead end in approaching his work – as does a polarisation into ‘narrative’ or ‘non-narrative’, with its implicit evocation of diverse approaches from film theory or aesthetics. In the chapter ‘Beware of Definitions’, this issue is discussed in greater detail and – in direct connection with the autobiographical elements inherent to his films and his self-image as a painter – an attempt is made to position his work in an individual fashion.

Super 8

Jarman, who grew up with the tradition of the classic home movie, extended this tradition while modifying it. In the early seventies, when he attempted to liberate himself from the outwardly imposed conventions of painting in that period, the Super 8 camera seemed to him like the ideal means to do so. Thus the images of his first Super 8 films displaced the impersonal, geometrical surfaces of his paintings. His camera became his brush, and light took the place of colour.

Chapter 5 analyses the shooting techniques he explored in connection with the process-oriented form of working that he developed – a practice which originated in the spontaneous and improvisational recordings of his first home movies and Super 8 films. His filming without a screenplay, which also originated in the early home movies, additionally demanded an extreme openness to chance elements and their unpredictable results: the camera became a part of everyday life. Finally, an exemplary exploration of the most representative films for each of five thematically grouped areas follows.

Cinema of Small Gestures

The aesthetic results that Jarman was able to achieve with his Super 8 films – but also the freedoms he enjoyed during the film-making process and his independence in terms of production – led him to continue to pursue the idea of developing the Super 8 format into a professional and recognised medium in the field of film. He called this the ‘cinema of small gestures’, and his films IN THE SHADOW OF THE SUN, THE ANGELIC CONVERSATION and IMAGINING OCTOBER belong in this context. The first two are discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

In December of 1986, one year after completing THE ANGELIC CONVERSATION, Jarman learned that he was HIV-positive. The topic of Aids had been omnipresent to him for years on account of numerous infections and deaths among his circle of friends and acquaintances. Nonetheless, the knowledge of his own infection brought about fundamental changes, for example, the direct politicisation in the themes of his remaining films or his direct and active political commitment to the gay rights movement.

Working with friends

However, 1986 was to become a decisive year not only because of his all-defining diagnosis with HIV, but for other reasons as well. Jarman was finally able to complete CARAVAGGIO, his first film on 35 mm, after spending years working on it. And it was also in the same year that he began with THE LAST OF ENGLAND, the film with which he would bid farewell to the 8 mm format. Only a few years before, Jarman had still been determined to professionalise the use of the Super 8 format in feature films, but after THE LAST OF ENGLAND he intensively turned his attention to working with 35 mm film; from then on, he used Super 8 only selectively.

Years later, he explained this turning away from 8 mm film through precisely that shift in content from the ‘documentation’ of private events or associative sequences of images to ‘concrete’ themes, whose appropriate formal realisation was now the focus of his interest. However, parting with Super 8 did not mean parting with the home movie and the ideas of the ‘cinema of small gestures’. On the contrary: for Jarman, work on 35 mm productions still meant the collective realisation of a project, and it meant working with friends – perhaps more so than ever. (…)

© Martin Frey: Derek Jarman – Moving Pictures of a Painter. p. 9 – 13.